Bowls and dishes are grouped together in Chapter 5 because they share essentially the same procedures for the first half of the glassblowing process. It is only when the vessels are attached to the punty that their processes diverge significantly.

Many bowls like the one shown in Figure 56 survive. They almost always have a Roman foot that is slightly downturned and conical. A ring of air is nearly unavoidably trapped within the fold that forms the foot.

The rim typically has a generously-sized outer fold. Experimentally, I have found that, in order to create a bowl with these proportions and have enough material at the top to make a large outer fold, there must be a tubular section of glass above the nascent bowl. This is consistent with my theory that Roman-period glassblowers nearly always formed a tube of glass, however short, between the blowpipe and the vessel’s body. In this instance, the tube ultimately disappeared in the final product, but its former presence is evinced in the form of the large outer-folded rim.

The most refined examples of these bowls have all-curving profiles. That is, the vessel wall between the foot and the rim is in some form of an “S” curve: no part of the wall between the convex portion (lower) and the concave portion (upper) is conical (straight line). Because this is technically difficult to achieve, few are exemplary in this regard (Vid. 38).

Interestingly, the form and proportions of bowls such as this one seem to have nearly universal appeal throughout broad periods of history. In the Roman world, they were made in pottery and silver as well as in glass. In Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) and later China, they were produced in porcelain, and in Renaissance Venice, opaque white glass (imitating porcelain) was employed. To name just one more of these few examples, in America during the Revolutionary period, such bowls were made in silver (including the “Revere” bowl).

Handles have been added to similar bowls. The grip handle (Fig. 57) permits a bowl to be picked up with greater traction and security (Vid. 39). The “trulla” handle (Fig. 58) transforms a bowl into a dipper. Two types of dipper handles are to be found in artifacts (Vid. 40).

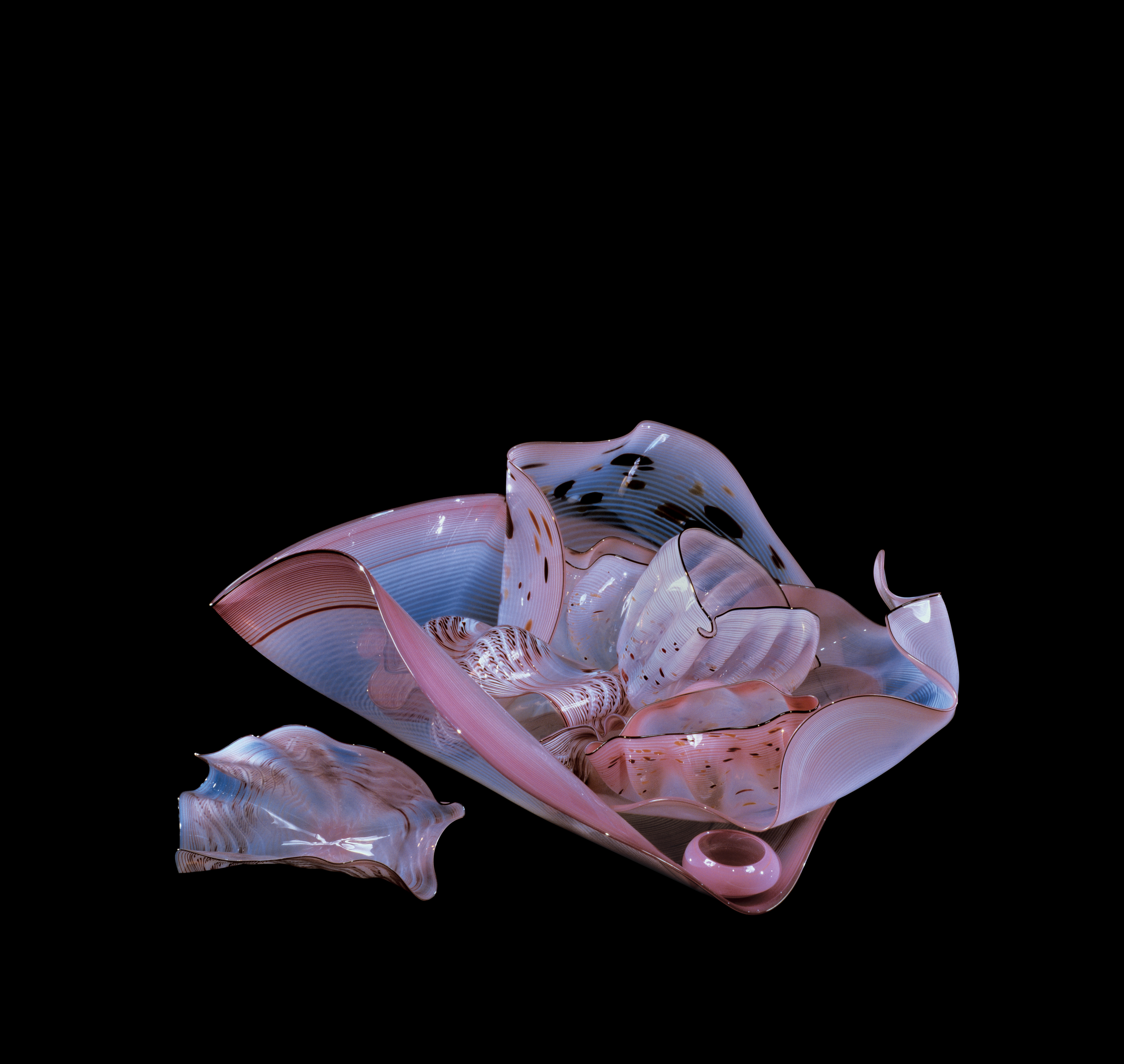

Glassblowing can be characterized as a series of processes developed to permit the close control of a soft, amorphous material that is considered by craftspeople to be notoriously difficult to control. The success of a commercial glassblowing enterprises such as Roman-period glasshouses depended on predictable processes. Therefore, when called upon to make handkerchief bowls such as the one shown in Figure 59, at least the last part of the process must have been fun for the artisans, compared with their other, more exacting work. As Video 41 shows, the final moments of the process involve a nearly uncontrolled spin of the punty. Another example is in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 60). The form and process were popular in mid-20th-century Venetian glass factories. There, they were called fazzoletto, the Italian word for “handkerchief” (Fig. 61.1, Fig. 61.2). Later, in the 1980s, the American studio glass artist Dale Chihuly made wide use of the technique in his “Basket” series (Fig. 62).

As was stated at the beginning of this chapter, typical Roman-period bowls and dishes (with Roman feet) differ only in the manner in which their final shaping processes were carried out. Thus, toward the end of the glassblowing process, the lower portion of the dish shown in Figure 63 was made much larger in diameter than that of a bowl such as the one seen in Figure 56. Their earlier processes were about the same (Vid. 42).

The dish in Figure 64 differs from the bowl in Figure 63 in only two respects. First, both the bubble and its Roman foot were made oval in shape. Second, the dish opened to a similar oval shape, while the bowl became round. This was the result of centripetal force caused by the rapid turning of the object while it was attached to its punty. It produced the final shape: the oval shape of the dish was extended outward as the object was spun (Vid. 43).